using CSV

using DataFrames

A = Matrix(DataFrame(CSV.File("MemorySeqHits_Cell2020_WM989_expt.csv")));

B = Matrix(DataFrame(CSV.File("MemorySeqHits_Cell2020_WM989_ctrl.csv")));What’s (not) wrong with the generalized singular value decomposition

The problem

Consider the following problem. We have data for a common set of variables (say genes) in two different conditions and are interested in finding common axes of variation in the data, for instance to find the dimensions along which the two datasets are most similar, or most different. For definiteness, let’s load an example of such data, consisting of gene expression data for a subset of 227 genes in one cell line (WM989) from the paper “Memory Sequencing Reveals Heritable Single-Cell Gene Expression Programs Associated with Distinct Cellular Behaviors”

The experiment data consist of 43 bulk RNA-seq samples of clonally related cells, whereas the control data consist of 47 samples of independent cells. Before proceeding let’s center and scale the data such that sample covariances can be computed directly as matrix products:

using LinearAlgebra

using Statistics

A .-= mean(A,dims=1);

A ./= sqrt(size(A,1));

B .-= mean(B,dims=1);

B ./= sqrt(size(B,1));Because the data are measured in transcripts per million the numerical range in the matrices is large. Rather than making a non-linear transformation, we scale each matrix by its norm (\(\|A\|=\mathrm{tr}(A^TA)\)). This way, since all operations below are linear, all results can easily be transformed back to the original scale if necessary:

A ./= norm(A);

B ./= norm(B);If we were interested in one dataset at a time, the obvious thing to do would be a PCA, or, equivalently, run the singular value decomposition (SVD). Now that we want to study two datasets simultaneously, perhaps the generalized SVD (GSVD) is what we need? In theory, yes, but as I’ll try to show, in practice, not without a bit of work.

Let’s jump straight in and see what the problem is. Computing the GSVD is as simple as:

E = svd(A,B);To understand the output, have a look at the LAPACK GSVD documentation, which matches the structure of Julia’s GeneralizedSVD type. If you need more background in linear algebra, consult Horn & Johnson’s Matrix Analysis. Technical details about the GSVD can be found in Golub & Van Loan’s Matrix Computations. The best source for an intuitive understanding of the GSVD is the article by Edelman & Wang.

According to the documentation or wikipedia, we should be able to form two diagonal matrices from the output, and indeed:

isdiag(E.D1'*E.D1), isdiag(E.D2'*E.D2)(true, true)The ratio of the values on these diagonals are the (squares of) the generalized singular value pairs, and the non-trivial ones (representing shared axes of variation) are those that are non-zero on both diagonals. Let’s have a look:

using Plots

using LaTeXStrings

p1 = plot(diag(E.D1'*E.D1), ylabel=L"\mathrm{diag}(D_1^TD_1)")

p2 = plot(diag(E.D2'*E.D2), ylabel=L"\mathrm{diag}(D_2^TD_2)")

plot(p1,p2,linewidth=2, layout=(2,1), legend=false)

xlabel!("GSVD index")That’s weird, there are no non-trivial generalized singular value pairs. Either we get a one in the first diagonal and zero in the second, or vice versa. In other words, the GSVD is saying that there are no shared axes of variation!

This is not what the data suggests though. For instance, let’s compute the SVD of each dataset separately:

EA = svd(A);

EB = svd(B);We can see that there is a pretty good overlap between the first few components in both datasets, which suggests there should be common axes of variation:

ncomp = 20

heatmap(abs.(EA.Vt[1:ncomp,:]*EB.V[:,1:ncomp]), aspect_ratio=1, yflip=true)

xlims!(.5,ncomp +.5)

ylims!(.5,ncomp +.5)

xlabel!("SVD index B")

ylabel!("SVD index A")These first few components are also the ones that explain most of the variation in both datasets:

varexA = EA.S.^2 ./ sum(EA.S.^2)

varexB = EB.S.^2 ./ sum(EB.S.^2)

p1 = bar(varexA[1:ncomp], ylabel="Var. expl. A", xlabel="SVD index A")

p2 = bar(varexB[1:ncomp], ylabel="Var. expl. B", xlabel="SVD index B")

plot(p1, p2, linewidth=2, layout=(2,1), legend=false)So why does the GSVD not detect these shared axes of variation?

The explanation

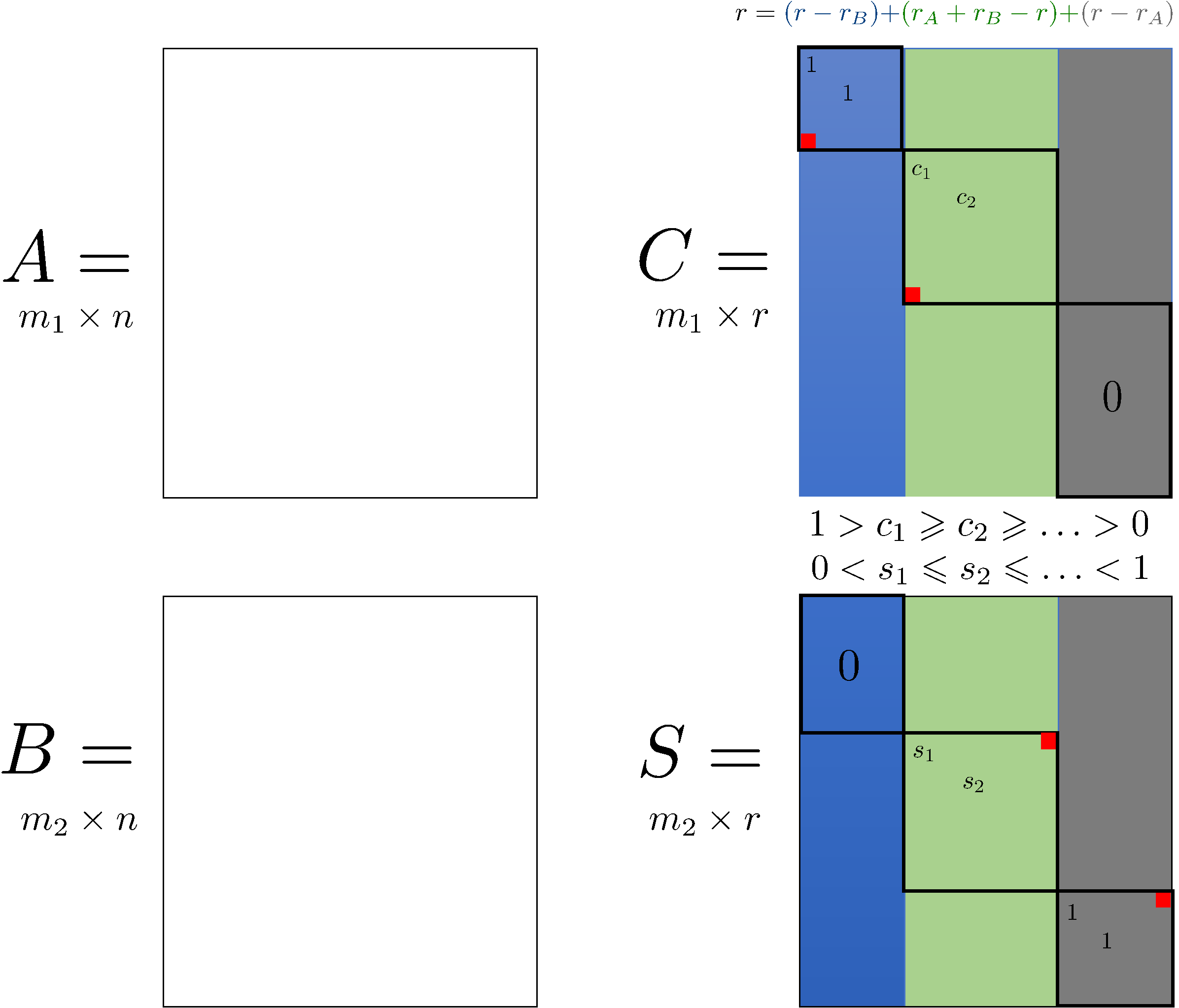

First, let’s be clear about one thing. There is nothing “wrong” about the GSVD result above, it is exactly what it should be according to theory. The easiest way to see this, is to use the visualization from Edelman & Wang (2019), whose Figure 1 is reproduced below. First compute some dimensions and ranks, following Edelman & Wang‘s’ notation:

m1,n = size(A)

m2,_ = size(B)

r = rank([A; B])

rA = rank(A)

rB = rank(B)

m1, m2, n, r, rA, rB(43, 47, 227, 88, 42, 46)We see that the rank \(r\) of the concatenated matrix

\[ \begin{pmatrix} A\\ B \end{pmatrix} \]

equals \(r=r_A+r_B\), where \(r_A\) and \(r_B\) are the ranks of \(A\) and \(B\), respectively. In that case we can see from the figure below that the green block with non-trivial (neither zero nor one) generalized eigenvalue pairs is absent indeed:

In words, this means that the row spaces of \(A\) and \(B\) are linearly independent subspaces of \(\mathbb{R}^n\). Hence they indeed have no common dimensions or axes of variation.

Why are the row the spaces linearly independent, when we saw in the figures above that they have a relatively high overlap and there are only a few dimensions that explain most of the variation in the data to begin with? Linear (in)dependence is a purely geometric and binary concept: two vectors or vector spaces are or are not linearly independent of each other. There is no notion of gradation and even a bit of noise in the data can cause two vectors to be linearly independent even when they manifestly represent the same underlying dimension. Consider the following example, where we add normally distributed noise with variance \(\delta=10^{-10}\) to a random vector of uniformly distributed values between zero and one:

using Random

v = rand(50);

δ = 1e-10

v1 = v .+ δ * randn(50)

v2 = v .+ δ * randn(50)

rank([v v]), rank([v1 v2]), norm(v-v1), norm(v-v2)(1, 2, 7.364840239506313e-10, 7.193190999314887e-10)Geometrically, the noisy vectors are linearly independent, even though they differ in norm by not more than a factor \(\delta\) from each other and the original vector.

Real data are much noisier than that, and hence it is no surprise that even if the experiment and control conditions share biological variability, the GSVD might tell us otherwise.

Denoising, part I

If noise in the data is the problem, maybe we can denoise the data? A simple denoising method is to use the SVD to remove dimensions from the data that explain very little variance. Here we keep enough dimensions to explain 99% of variance in the original data and remove the remaining ones:

cut = 0.99;

icutA = findfirst(cumsum(varexA) .>= cut);

icutB = findfirst(cumsum(varexB) .>= cut);

A_denoise = EA.U[:,1:icutA] * Diagonal(EA.S[1:icutA]) * EA.Vt[1:icutA,:];

B_denoise = EB.U[:,1:icutA] * Diagonal(EB.S[1:icutA]) * EB.Vt[1:icutA,:];To check if this removes the linear independence issue, we only need to check the ranks of the relavant matrices:

rA_denoise = rank(A_denoise);

rB_denoise = rank(B_denoise);

r_denoise = rank([A_denoise; B_denoise]);

rA_denoise, rB_denoise, r_denoise(12, 12, 24)The problem is still there: the rank of the concatenated matrix equals the sum of the ranks of the denoised data matrices and hence their row spaces are still linearly independent.

Denoising, part II

If the rank of the concatenated matrix determines whether the GSVD will succeed in finding common axes of variation or not, maybe we should do the denoising at the level of this matrix instead? First we verify that most variation in the concatenated matrix is also explained by a small number of dimensions:

Econcat = svd([A; B]);

varexAB = Econcat.S.^2 ./ sum(Econcat.S.^2)

bar(varexAB[1:ncomp], linewidth=2, legend=false)

xlabel!("SVD index")

ylabel!("Variance explained")Hence it makes sense to apply the denoising technique on the concatenated matrix. By construction, the concatenated and individual denoised matrices will now all have the same rank:

icutAB = findfirst(cumsum(varexAB) .>= cut);

AB_denoise = Econcat.U[:,1:icutAB] * Diagonal(Econcat.S[1:icutAB]) * Econcat.Vt[1:icutAB,:];

A_denoise2 = AB_denoise[1:m1,:];

B_denoise2 = AB_denoise[m1+1:end,:];

rank(A_denoise2), rank(B_denoise2), rank(AB_denoise)(14, 14, 14)We can now run the GSVD again on the reconstructed data matrices1:

E_denoise = svd(A_denoise2,B_denoise2);Sort the generalized singular value pairs by their value in the \(A\) matrix and plot. We also plot the angle \(\theta = \arctan(S/C)\) (see Edelman & Wang).

d1 = diag(E_denoise.D1'*E_denoise.D1)

per = sortperm(d1, rev=true)

sort!(d1, rev=true)

d2 = diag(E_denoise.D2'*E_denoise.D2)[per]

p1 = plot(d1, ylabel=L"C^2")

p2 = plot(d2, ylabel=L"S^2")

p3 = plot(atan.(sqrt.(d2./d1)), ylabel=L"θ", ylims=(0,π/2), yticks=(0:π/8:π/2, [L"0", L"\pi/8", L"\pi/4", L"3\pi/8", L"\pi/2"]) )

plot(p1, p2, p3, linewidth=2, layout=(3,1), legend=false)

xlabel!("GSVD index")Now we see a nice gradation where some generalized SVD dimensions are mainly in the direction of \(A\), some mainly in the direction of \(B\), and several that are intermediate between \(A\) and \(B\).

Finally, to find the representation of the GSVD dimensions in gene space, we need to construct the matrix called \(H\) in Edelman & Wang (see their page 2):

H = E_denoise.R0 * E_denoise.Q'14×227 Matrix{Float64}:

0.00447095 0.002604 0.127807 … -0.000196583 -0.00582014

-0.00362387 -0.00146396 0.0205381 -0.00056616 0.0022589

-0.00254524 6.48104e-5 0.0149079 0.000328387 -0.00792761

0.000634473 0.000326485 0.0771422 -0.000665398 0.00549493

-0.00136469 -0.000866736 0.144786 -0.00583675 0.0022284

-0.000222969 0.000722116 0.176814 … 0.0025655 0.000307955

-0.0023383 -0.00144977 -0.035089 -0.000517691 0.00216125

-0.000622941 -0.00100678 0.0409441 0.000244277 0.00631847

-0.00272642 -0.00203296 -0.0272976 -0.0102 -0.00568522

-0.00234279 -0.000711262 0.0705138 -0.00153576 -0.00381339

0.000205715 0.000990202 0.0675681 … -0.000350449 0.00174835

0.000749081 -0.00037692 0.00512842 -0.00167819 0.00232646

-2.59317e-5 0.000328109 0.00911318 -0.00309483 -0.00228416

-0.00162327 -0.000778512 -0.0401655 0.000129554 -0.00307492Footnotes

Note that the first step in the GSVD construction is to compute the SVD of the concatenated matrix. For large matrices, it makes no sense to first compute this SVD, then reconstruct the original matrices, and then compute the same SVD again in the GSVD call. In that case it’s better to implement the different steps of the GSVD construction manually keeping only the first few components of the SVD of the concatenated matrix.↩︎